This post is originally published by the Web Foundation, in “Open Data & the OGP Founding 8: Where Are They Now?”, dated 6 December 2016. Image © Descrier descrier.co.uk, CC BY 2.0

Five years on from the founding of the Open Government Partnership, how are the original OGP members faring on the implementation of open data? The answer is mixed.

Since its inception, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) has grown from eight to 70 governments who have agreed to National Action Plans (NAPs) designed to improve openness in government. Over 2,450 commitments have been made in these NAPs. Of these, over 40 governments have made more than 230 commitments to incorporate open data as a key tool for reaching governance goals.

Open data forms a core pillar of what we envision as digital citizenship for the 21st Century: empowering citizens to use open data and the open Web to play an active role in decision-making for their communities. So we wanted to know: how are the founding eight OGP member states faring in improving the availability of open data need to tackle corruption, improve transparency, increase citizen participation and enhance efficiency in public service delivery?

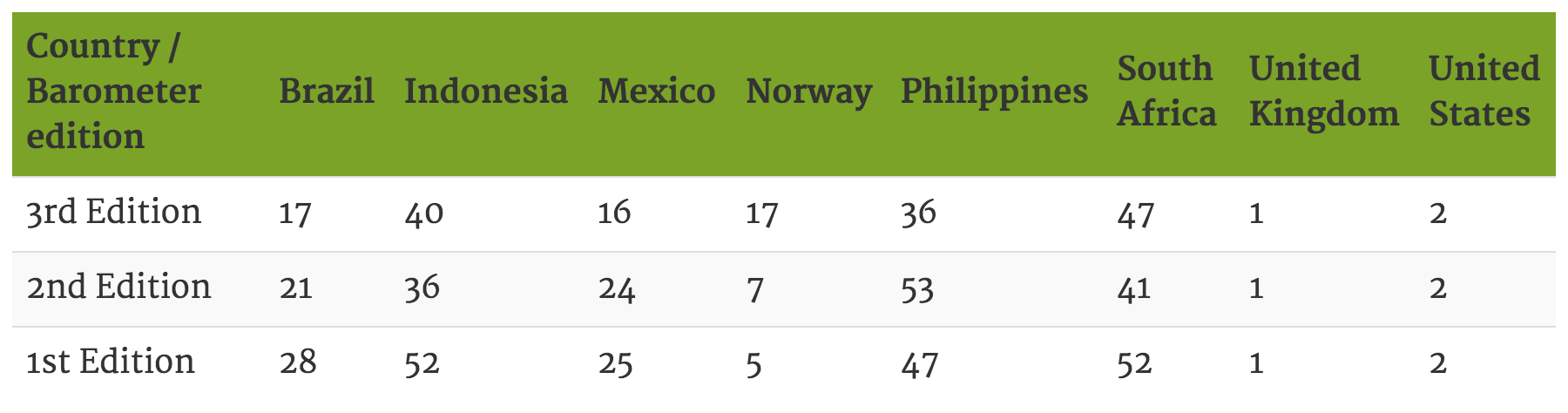

To spot check progress so far, we decided to use the Open Data Barometer – our 92 country study of readiness, use and impact of open data at the national level – to look at how the OGP’s founding eight members – Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, South Africa, United Kingdom, and the United States – have progressed over the Barometer’s three editions. The findings are mixed:

Rankings from the last 3 published editions of the Open Data Barometer

Overall, our analysis shows that open data policies are typically in place, and the number of open datasets has increased. However, when we dig a little deeper, it is clear that many flaws still remain. In many cases, we are missing more detailed data that would make these datasets truly useful for citizens. The quality of datasets also varies widely. Meanwhile, datasets crucial to governance – such as spending and company data – are least likely to be open or available at a detailed level. (Details by country below)

While we are encouraged by the progress made on the number of open datasets, we also acknowledge there is much work to be done and quantity alone isn’t enough. The Open Data Charter is emerging as a go-to community to support these efforts, yet only three of the eight founding OGP members – Mexico, Philippines and the UK – have so far adopted it. We urge all OGP members, who are meeting in Paris this week, to take a look at open data quality and completeness in the next phase of open data implementation to ensure that the most relevant datasets are available for use and reuse. Five years on, it is clear our work has only just begun and we must move beyond policy to practice and impact.

How are each of the founding eight progressing?

Brazil

Brazil has made improvements with strong implementation of open datasets for social policy, for example with the QEdu education initiative. Yet, data in other areas remain closed – for example economic data. Although some efforts have been made to improve the availability of spending, budget and contract data, and there is still no open company register. To tackle corruption and its impact on society, Brazil must make these data available. It is also worth noting that there is still no specific legislation on data protection, despite discussions around a specific law addressing personal data protection that have been ongoing since 2012.

Indonesia

Indonesia made significant improvements in open government data a couple of years ago, but progress has since slowed. Given the lack of support for innovation and availability of training, open data readiness is particularly weak for entrepreneurs and businesses. Furthermore, city and regional activities are very limited beyond the Province of DKI Jakarta, the cities of Bandung and Banda Aceh, and the regencies of Bojonegoro and Semaran. Positive steps have been taken in 2016, with the government planning to release its national open data initiative. To advance open data in the country, it will be critical to publish key datasets as open data, including spending, budget and contract data.

Mexico

Mexico is a new challenger among the founding eight, with climbing the Barometer ranking thanks to new policies that aim to improve public service delivery. Similarly to Brazil, Mexico has focused on social objectives, for example through the the Mejora tu Escuela education initiative. Mexico has shown improvement in the availability of budget data and has made astrong commitment to opening contract data through the Open Contracting Data Standard as well as through its adoption and lead stewardship of the International Open Data Charter. However, there is still clear progress to made in using open data to tackle corruption. For example, one of Mexico’s weaknesses, as is the case with many of the founding eight, is the absence of detailed open spending data that allows citizens and civil society to verify whether tax revenues have been spent as promised.

Norway

Norway is the only one of the founding eight OGP members that has had an overall decline in its Barometer ranking. Even though the groundwork to prepare for open data remains strong, support for innovation and implementation is weak. Open data and data management policies could be improved and several other readiness components (engagement with CSOs, training availability and subnational initiatives) are now at a standstill, while the other countries have been making consistent improvements. Open data has helped Norway improve improve efficiency across government, often as a result of open budget data. However, when it comes to accountability, spending data is still not available at detailed level to allow citizens to verify if budget promises were kept.

Philippines

The Philippines has made the greatest improvement regarding open government data readiness, in comparison to the other founding eight. But the strong foundation laid for open data – through policies and increased budget for open data initiatives, has not translated into implementation and impact. The only exception to this trend is data related to innovation such as national maps, transport timetables and public contracting. The country also lacks proper data management policies, has not yet enacted the Freedom of Information (FOI) Bill, though the current President has signed an Executive Order on FOI and has launched an online portal for filing information requests. In terms of open data availability, the Philippines mirrors its counterparts with an improvement in the availability of open budget data, but failing to provide open and detailed spending data.

South Africa

South Africa has made modest improvements, but the open data environment and implementation is still quite weak in spite of commitments it has made on open data through the G20. The release of budget data has been a bright spot, CSOs have used this data for advocacy and influencing budget allocations within government. The Municipal Money open data portal has been an important part of increased budget transparency at the subnational level. In spite of this step forward on budgeting data, the broader picture is still very weak. The government is lacking official policies for government open data and data management and existing open data initiatives in the country are quite weak across both national and subnational government. In general, data availability and accountability is limited. In terms of impact, serious efforts remain to be made on increasing government efficiency and effectiveness, and increasing transparency and accountability. Civil society and technology professionals must also become more engaged to drive the open data agenda forward.

United Kingdom

The UK is strong overall, consistently holding first place ranking in the ODB since its first edition in 2013. However, progress has stalled lately, with room for improvement in many fields, including data management and data protection policies. The country has a good level of open data availability, but quality and granularity of several datasets could be improved. Considerable impact has been made in all areas – readiness, implementation and impact – except for the inclusion of marginalised groups. The country can also improve on political impact for both efficiency and transparency. And going forward, could this year’s political changes affect future performance?

United States

The US has consistently held the second place ranking in the ODB since its first edition. But like the UK, it has recently stagnated, with few advances while other countries have made gains to catch up – as the current tie in ranking with France demonstrates. Overall, open data policies are in place, but data protection measures and the implementation of right to information could be improved. Open data has had the most consistently strong impact on the economic aspects of citizens’ lives, with its impact on social and political aspects still remaining quite limited. Overall, there remains room for improvements on data quality and completeness with company and land ownership data standing out as a critical area that is lagging behind. And much like the UK, it is an open question whether the political leadership transition might affect open data policy and implementation in future.

To read more about results from the Open Data Barometer, visit the website and data explorer atopendatabarometer.org or get in touch with our research team at OGP:@carlosiglesias@anabmap

Leave a Reply